Michael Smith Gallery

Antique Navajo and Pueblo Textiles

Antique Pueblo and Navajo Weavings

Brief History of Pueblo Weavings

The sixteenth-century Spaniards, entering the region we know today as the American Southwest, found the natives of the land living in compact villages, or pueblos, of stone-walled or mud-walled houses. These Indians practiced intensive agriculture, had a complex socioreligious system, and were skilled in many crafts, especially pottery making, basketry, and weaving. Spanish reports suggest that there were at least seventy villages in the mid-1500s (Schroeder 1979:236-54). The contemporary Pueblo Indians, descendants of these earlier people, live in thirty-one villages: nineteen in New Mexico and twelve in the Hopi country of northeastern Arizona.

The Spaniards noted especially that the Indians they encountered from the vicinity of present-day El Paso northward were well clothed in cotton textiles, in marked contrast to the generally naked peoples they had previously met in their march north from the Valley of Mexico. Spanish accounts express astonishment at the beauty and quantity of the fabrics worn by the people and offered as gifts. They mention embroidered and painted shirts, mantas or shawls, sashes, and kilts or breechcloths, though they give little precise information about technical processes or design styles. Luxan, on the occasion of Antonio de Espejo’s visit to Awatovi in 1583, recorded: “Hardly had we pitched camp when about one thousand Indians came laden with maize, ears of green corn, pinole, tamales, and firewood, and they offered it all, together with six hundred widths of blankets small and large, white and painted, so that it was a pleasant sight to behold” (Hammond and Rey 1929:98).

We know that the kinds of textiles seen by the Spaniards had been made and used by southwestern people for hundreds of years (Kent 1957, 1983). Our evidence consists of some 3,000 textile fragments and a few complete fabrics from archaeological sites dating mostly between A.D. 1000 and 1400, and of costumes depicted in the fifteenth-century Pueblo murals of Kuaua, Awatovi, Kawaika-a, and Pottery Mound (Dutton 1963, Hibbgen 1975, Smith 1952). The oldest examples of Anasazi, or prehistoric Pueblo, textiles, dated between A.D. 200 and 600, were made by finger techniques from wild plant and animal fibers. Cotton, which was introduced into southern Arizona between A.D. 100 and 600, appears in a few of these Anasazi textiles shortly before 700. Loom-woven cotton fabrics have been found in a few northern sites dated between 700 and 1000, but the first clear evidence for the cultivation of cotton north of the Mogollon Rim dates after A.D. 1000.

In addition to using native-grown cotton, early Pueblo weavers worked with apocynum (Indian hemp), yucca leaf fiber, fur, and feather cord. Tools found in many of the prehistoric sites indicate that cotton was spun with the same type of stick-and-whorl spindle still in use today. The resulting yarn was fashioned by finger processed into socks, bags, nets, and braids or was woven into cloth on a wide upright loom or a backstrap loom. Weaving on the loom was a man’s art and continued to be so until recently. Anasazi weavers knew a limited range of natural dyes, including brick red, brown, black, yellow, and pale blue.

At the time of their arrival, the Spaniards found cotton growing at pueblos in the Rio Grande Valley as far north as the mouth of the Chama River, at Acoma, and at Hopi to the west (Jones 1926). Spanish accounts are unclear about whether the plant was grown at Zuni, although Fray Marcos de Niza in 1539 spoke of Zuni houses that were full of cotton cloth (Riley 1975:139). Judging from the historical accounts, it is probably safe to assume that some of this cloth was woven at Zuni but most was obtained from the Hopi villages, where cotton was grown in great quantities to supply a thriving industry that produced textiles both for domestic use and for export., Luxan, for example, described in 1583 a march of two leagues, one of them through cotton fields” between the first and second Hopi mesas (Hammond and Rey 1929:101).

During the sixteen century, the Zuni towns sat at the crossroads of major trade routes running to the south and southwest, northwest toward the Hopi country, and north and east to the Rio Grande Valley, Pecos Pueblos, and the southern Great Plains. Cotton cloth was surly important among the goods carried along these routes. Trade goods passing through Zuni and other pueblos included turquoise from New Mexico, shell and coral from Gulf of California and the Pacific, parrot and macaw feathers from Mexico, worked hides from the Great Plains, salt and semiprecious stones from various localities, and blankets from Hopi.

The Indian Leaflet Series of the Denver Art Museum, written b y the late Frederic H. Douglas between 1930 and 1940, remains a basic source of information about the textiles of the Rio Grande Pueblos, Acoma, Laguna, and Zuni. Leslie Spier’s 19724 paper adds substantially to the information on waving at Zuni at the turn of the century. There is a bit more information in print for the Hopis (See Colton 1938 and 1965), Douglas 1938, Hough 1918, Kent 1940, Stephen 1936, Whiting 1977, and Wright 1979), but our knowledge of the history and use of some textiles remains incomplete.

There is a good reason for the general lack of public knowledge about, and interest in, Pueblo textiles. Quite simply, they were woven not for tourist sale but to meet the needs of an internal market. Except for a few forms such as belts, sashes, and certain contemporary embroideries, they have not proved usable by Anglo buyers. The modest number of blankets and rugs woven for external markets has never commanded the attention that has been given to Navajo textiles (Kent 1976).

The history of Pueblo textiles since the arrival of the Spaniards in 1540 is best considered in four time periods: the period of Spanish domination, 1540 – 1848; the “classic” period of historic Pueblo weaving, 1848 – 1880; the period of growing Anglo-American influence and the decline of weaving, 1880 – 1920; and the revival of certain forms of Pueblo textiles that led to the contemporary picture, 1920 – 1950.

Navajo Weavings

Navajo weaving has captured the imagination of many enthusiasts, not only for its aesthetic qualities – its variety of design and general excellence of technique – but also because its stylistic changes through time to faithfully mirror the social, economic, and political history of the Navajo people. It is as though the women wove their life experiences into their textiles, giving us insights into their changing world.

Navajos say they learned to weave from Spider Woman on a loom constructed according to directions given them by Spider Man. A more mundane view is that weaving as practiced by the Navajos is an eclectic art, learned from the Pueblo Indians in the mid-seventeenth century and reflecting both Pueblo and Spanish clothing styles and design preferences for the next 150 years. By the late 1700s, commercial European and Mexican trade cloth, which could be raveled for red yarns, modified the appearance of some Navajo textiles; and a few decades later, variously colored commercial yarns and strong Mexican influence in the form of the Saltillo design style changed them still further. Since about 1850, the major agent of change has been Anglo-Americans, who not only introduced bright aniline dyes but also, by furnishing ready-made clothing and commercial cloth, lessened the Navajos’ need for their own loom products and turned the weavers towards an off-reservation market. Shortly before 1900, Anglo-American fostered radically new design motifs to be used on rugs rather than traditional blankets.

Navajo weavings may be classified for descriptive purposes under three major stylistic periods: the Classic, 1650 to 1865; the Transition, 1865 to 1895; and the Rug, 1895 to the present. These terms ere first proposed by Charles A. Amsden in 1934; I have modified his opening and closing dates in some cases so that they correlate with significant historical events affecting the Navajo people.

Throughout the Classic period, Navajo weavers directed much of their time and energy toward producing clothing for their own people. They wove woolen articles very similar to those that the Pueblo Indians had designed and made of cotton long before the coming of the Spaniards. Outstanding among these were mantas—rectangular blankets wider, measured along the wefts, than they are long—which were worn as wraparound dresses by women and as shoulder robes by both sexes. The Navajos also made tuniclike shirts, breechcloths, harrow hair ties, and garters for men, and warp-patterned belts for both men and women. By 1700, Navajos as well as Pueblos were probably weaving wool serapes, or Spanish-style blankets longer, measured along the warps, than they are wide. The shape, the use of wool yarns and indigo dye, and probably the common pattern of simple stripes all resulted from Spanish influence.

Surplus products of the Navajo loom, particularly mantas and serapes, gained increasing importance in trade with Pueblos, other Indians, and Spaniards from 1700 to the late 1800s. With the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821, the market for Navajo blankets expanded still further to include Anglo-Americans. In the last years of the nineteenth century (that is, during the Transition period), the Navajos wove less clothing for themselves and more blankets and serapes for trade with their traditional customers and Anglos as well. With the conversion of blankets to rugs just before 1900, weaving became essentially market oriented, though saddle blankets were, and still are, made for local consumption.

There has never been a time in the long history of Navajo weaving when the artists were not aware of the needs of the marketplace nor failed to modify their work to some extent to suit the tastes of potential buyers. This flexibility, coupled with the introduction of design ideas from other cultures and of new dyes and commercial yarns in a range of colors unknown to weavers of the eighteenth century, inevitably changed the appearance of Navajo textiles. Contemporary rugs bear little or no visual resemblance to textiles of the Classic period, and we may not be able to find single set of aesthetic principles expressed in all the various historical styles. The evolution of Navajo textile design cannot be understood, however, simply as a function of the myriad influences brought to bear on weavers over the centuries. It is the creative ways in which new ideas and materials were handled that will engage our attention. Navajo weavers struck a balance between eclecticism and originality.

The origin and evolution of Navajo weaving from about 1650 to the early 1980s, as recounted here, is quite well documented, but the story has by no means ended. Change continues as weavers experiment with new materials and new combinations of design motifs. Undoubtedly the principal motivation for the perseverance of weaving is monetary return, but the art is also cherished, as it might well be, by many Navajo as a distinguished product of their traditional culture.

Source: Pueblo Indian Textiles, A Living Tradition, by Kate Peck Kent, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Source: Navajo Weaving, Three Centuries of Change, by Kate Peck Kent, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Mantas

Mantas were woven with all cotton, all wool, or a combination of the two. The early wool mantas (c.1800-1890) had a natural brown wool center done in a diagonal twill weave, with end panels dyed in indigo blue woven with a diamond twill technique. After about 1880 to 1885, the centers and ends were over-dyed black. The Zuni type is distinguishable from the Hope by the inclusion of three raised ridges (referred to as “hills and valleys”) above both end panels. Mantas from the northern Rio Grande pueblos are simpler than those of the Hopis and Zunis.

Mantas were woven with all cotton, all wool, or a combination of the two. The early wool mantas (c.1800-1890) had a natural brown wool center done in a diagonal twill weave, with end panels dyed in indigo blue woven with a diamond twill technique. After about 1880 to 1885, the centers and ends were over-dyed black. The Zuni type is distinguishable from the Hope by the inclusion of three raised ridges (referred to as “hills and valleys”) above both end panels. Mantas from the northern Rio Grande pueblos are simpler than those of the Hopis and Zunis.

Pueblo Dresses

Unlike Navajo dresses, which are woven in two separate panels and stitched together, Pueblo dresses are basically woolen mantas that are folded in half. They are worn under the left arm, pinned on the right shoulder, and belted at the waist. As with mantas, the end panels are usually done in diamond twill and the center in diagonal twill. Until the early 1880’s, the ends were dyed with indigo and the centers were natural brown; later, dresses were dyed black.

Dress and manta weaving died out in the Rio Grande pueblos by the early 1880’s, but continued at the Hopi and Zuni villages. Today, the traditional costume has become almost totally Americanized: Anglo-American clothing predominates, with the addition of fringed shawls. Traditional garments are now worn only at ceremonies and special occasions.

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

“Lazy Line,” or the diagonal edge between segments of weave in a Navajo blanket.

Comparison of Southwest Textile Traits:

Lazy lines very rare (Hopi); some lazy lines (Zuni); lazy lines common (Navajo); no lazy lines (Spanish Colonial).

With the exception of a few Navajo blankets in which the design extended completely to the ends of the fabric, Navajo and Pueblo weavers began by weaving a number of wefts completely across the fabric, forming a solid band of either the ground color or a contrasting color. Above this, however, depending on the width of the textile, Pueblo and Navajo weavers usually employed different methods to weave the body of the fabric.

Because most Pueblo textiles were woven in only two or three solid colors or were decorated mainly with weft stripes, Pueblo weavers, for the most part, interlaced the wefts continuously from edge to edge of the loom. Only limited use was made of complex woven figures that required the use of discontinuous wefts, that is, tapestry weave.

On the other hand, if the fabric was more than about 30 inches (75 cm) wide, Navajo weavers tended to weave the textile in segments. Because the batten generally was only about 30 inches (75 cm) or so in length, the amount of shed opened for the weft passage at any one time did not exceed that width. Instead of moving over and opening a wider shed to carry the weft completely across, the Navajo weaver usually continued to weave upward in one area, dropping back one warp with each weft pick, thus leaving a diagonal edge to that segment. Then the weaver would move over and weave another segment against the first one, filling the gap left by the preceding unit and leaving a subtle diagonal line in the fabric. This has come to be termed a “lazy line”. Lazy lines may cross both ground color and pattern areas.

Weaving in obvious segments divided by lazy lines is predominantly a Navajo trait. It was used occasionally by the Zunis and even more rarely by the Hopis. We understand too little about the blanket weaving of the Rio Grande Pueblos to know how commonly it was used there, if at all.

Source: Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, Joe Ben Wheat, edited by Ann Lane Hedlund; University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ, Copyright 2003 The Arizona Board of Regents (Pages 4, 104, 105)

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

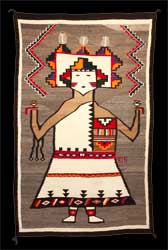

As rules go, it is usually found in the upper right hand corner as the weaver saw herself leaving the box (border) so that her creativity will not be trapped. It is a place for the spirit to pass. Not all weavers believe this. You may find a lot of rugs do not have a spirit line. However, we also have a rug that has two spirit lines.

For those weavers who believe in putting in a spirit line, they may not always follow the rule to put it in the upper right hand corner. We have a rug that the weaver put in a spirit line at the bottom of the rug as she was beginning the weaving. She was about to weave the Hopi Kachina Figure, so she wants to free herself first rather than wait until the end.

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

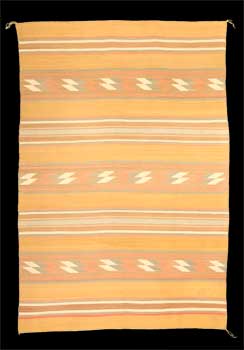

(Chinle - It flows from the canyon.)

Elevation: 5058’

Location: Gateway to Canyon de Chelly area, northeastern Arizona. (Spanish corruption of the Navajo word “tseghi,” meaning “rock canyon,” with the English pronunciation a further corruption from the Spanish),

Established: 1882 – first known merchant. 1886 – first valid license issued to Lorenzo Hubbell, of Ganado, and his partner C. N. Cotton. Business was poor at the first Chinle store and Hubbell let his operating license lapse the following year. In 1900 he returned to the Chinle area and constructed a second post on the site of today’s post office. Realizing the tourist potential of Canyon de Chelly, Hubbell built an elaborate two-story rock hostel to accommodate guests; the floor level serving as the trading post. Hubbell’s foresight for tourism was correct, but it was about 30 years premature. The “no cars – no roads” environment of the Reservation forced a second withdrawal in 1918 when he sold the holdings to his partner, Cotton. Later a tri-partnership of Camilo Garcia, Leon H. (Cozy) McSparron, and Hartley T. Seymour bought all three posts in the area and concentrated their business back at the mouth of the canyon.

THE RUG: Trader Leon H. (Cozy) McSparron is responsible for the Chinle style rug. His experiments with dyes both vegetal, and commercial, provided impetus to his weavers to revive the simple stripes and bands of the Early Classic Period, (1700-1850). The modern Chinle rug has maintained the McSparron suggestion and today reflects the combination of both vegetal and aniline dyes. It is generally considered; however, that the contemporary Chinle is basically vegetal. Commercial dyes are used sparingly to outline or accentuate the smaller designs. The borderless rug has a spacious feeling with

small terraced designs and squash blossoms encased in broad bands. Some of the intervening stripes use the Crystal “wavy line” techniques. The weavers in the district create an attractive rug of pleasant balance. Natural white wool usually provides the background, with less used shades of vegetal-dyed green, brown, and gray. Rose colors and yellows are favorites, along with aniline black to denote outlines and termination panels at the ends. The rug is distinctive and well-woven. Some pieces must be closely examined to distinguish them from a Crystal or Wide Ruins. One of the keys is the color utilization, part vegetal and part aniline. Also, the weave is somewhat heavier than its all-vegetal neighbors.

Still another effort to change the course of Navajo weaving was undertaken by Mary Cabot Wheelwright, a Boston philanthropist and amateur anthropologist. Working with Cozy McSparron, referenced above, Wheelwright supplied photos of old blankets to the weavers, and the cash to buy their first efforts, beginning in the early 1920’s. Wheelwright preferred the 19th century classic pieces with their primarily horizontal borderless patterns, rather than the bordered oriental-style rugs common elsewhere on the Reservation. She also encouraged softer colors derived from native dye plants. The first dye experiments produced shades of gold and green, but soon weavers experimented with more dyes to get an extraordinary range of colors not seen in older weaving. This vegetal revival style became very popular and was taken up by other traders, first at Wide Ruins in 1936, and then at Crystal around 1940.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Pages 64, 66, 67).

Source: Weaving of the Southwest, Marian Rodee, 1987, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, (Page 99).

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Location: Washington Pass, NM, high in the Chuska Mountain Range, west of Highway 666 that leads from Gallup to Farmington. (New Mexico)

Location: Washington Pass, NM, high in the Chuska Mountain Range, west of Highway 666 that leads from Gallup to Farmington. (New Mexico)

Established: In 1896, John B. Moore from Sheridan, Wyoming purchased an interest in the post, originally established in 1894 and known as Cottonwood Pass. In 1897 he purchased the entire interest in the post and renamed it “Crystal” after a very pure and sparkling mountain spring that ran by the post. He left the Navajo Reservation in the autumn of 1911.

The remoteness of the Crystal area and the fact that winter business was fairly limited led Moore to issue a mail order catalog, a newly developed American merchandizing technique popularized by Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward. He starts off his first catalog of 1903 thus:

“While this Booklet makes no claim of being a pioneer in its field, I think it may justly claim to be the first of its kind published and distributed from the very center of the Navajo Indian Reservation by an Indian Trader living among and dealing directly with the Indians who make the goods which it illustrates and describes.”

THE RUG: Moore obviously had a strong feeling for Navajo weaving and this comes across in his catalogs. He was instrumental in promoting a bordered rug style, more suited to the tastes of Anglo buyers. However, all the styles in his 1903 catalog, and the individual leaflets, are based on traditional Navajo weaving patterns common in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, sometimes with borders added, sometimes almost indistinguishable from blankets of twenty to thirty years earlier. Designs included “Old Chief Pattern”, diamonds, cross, whirling logs, etc. Many of the rugs were three-color of red, white and black; gray, black and white; also natural brown and indigo blue, or navy.

The following is an excerpt from the 1903 catalog. “A word as to colors: It will be noted that in the illustrations only white, red, black, navy and gray appear. As a matter of fact a blanket may have a little orange, green, or yellow, one or more of these colors in it; but very few have, and these will never be sent except upon special request to any mail order customer. I have no purples, magentas, browns, etc. to send any one. Faulty colors make inferior blankets, and all second and first grades will be in good and perfect colors.”

We can assume that Moore and his wife were very successful with their mail order business for a larger, more impressive, catalog was issued in 1911. It is Moore’s 1911 catalog that shows a real change in the styles being produced at his post with the much discussed oriental rug motifs with multiple borders, large central medallions, and with numerous hooks, “airplanes”, and filler elements in the background. It is this catalog which presents the new “oriental” type patterns which were to take over the rug market in the twentieth century, moving from Crystal to Two Grey Hills to Ganado, with regional variations in coloration.

Moore left the Navajo Reservation in 1911, and his influence lived long after him. His partner, Jesse Molohon, continued the business and the styles that Moore and his best weavers developed long afterwards. In fact, the old styles did not end at Crystal until around l940, as reported to Frank McNitt by Desbah Nez, daughter if Yeh-del-spah-bi-Man, one of Moore’s weavers.

Moore was one of the great pioneers in the field of Navajo weaving and was instrumental in changing it from blanket to rug. He, along with other traders of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, saw that the future of weaving lay with adapting to the changes in Anglo taste, adaptations that are still being carried on by weavers and traders working together.

Around 1940, a vegetal revival style was taken up by Crystal. Mary Cabot Wheelwright, a Boston philanthropist encouraged weavers to develop and use softer colors derived from native dyed plants. The first dye experiments produced shades of gold and green, but soon weavers experimented with more dyes to get an extraordinary range of colors not seen in older weaving.

Source: J. B. Moore, United States Licensed Indian Trader, The Catalogues of Fine Navajo Blankets, Rugs, Ceremonial Baskets, Silverware, Jewelry & Curios, originally published between 1903 and 1911, New Material copyrighted 1987, Avanyu Publishing, Inc., Albuquerque, NM (Pages 1, 2, 3, 23)

Source: Weaving of the Southwest, Marian Rodee, 1987, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, (Pages 89, 99)

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Hubbell Trading Post at Ganado

Elevation: 6400’

Location: Ganado (Spanish meaning “herd of cattle”) is situated on the crimson shale plains midway between the Defiance Plateau on the east and the Hopi mesas to the west. (Arizona)

Elevation: 6400’

Location: Ganado (Spanish meaning “herd of cattle”) is situated on the crimson shale plains midway between the Defiance Plateau on the east and the Hopi mesas to the west. (Arizona)

Established: 1871, and then sold to Juan Lorenzo Hubbell in 1878. Hubbell, in honor of his friend and Navajo Chieftain Ganado Mucho (Spanish for “many cattle”) is responsible for the current place name. (Often, Hubbell Trading Post is called Ganado Trading Post) From this headquarters, Hubbell later formed a partnership with C.N. Cotton who bought a half interest in the post in September of 1884.

Cotton was industrious and had a keen interest in business. The trading post was much more than a local grocery. The trader had to buy what the Indians produced because this income was what the Indians then used to buy goods from the trader. The Indians had unlimited time, and if the trader didn’t pay a fair price for their goods, the Indians would go to another post to trade. If the trader priced his goods too high, again the Indians would go elsewhere. The smart traders learned that the only effective way to deal with the Indians was in the Navajo language. Cotton understood this and soon learned the language.

After running the trading post for a while, both Cotton and Hubbell decided to demand that the Navajo improve the quality of the blankets which were brought to the trading post for sale. Hubbell was a man who respected traditional Navajo culture and hence urged the weaving of Navajo blanket patterns. Cotton prodded the weavers to produce blankets of better quality and to make more of them. He sent letters to dealers in the East, to Tiffany & Company in New York, to San Francisco, and to Denver extolling the virtues of the Navajo blanket. Cotton noted the bright aniline dyes brought in to Fort Defiance by the trader Ben Hyatt. Hubbell was particularly fond of the dark red dye, since called Ganado red, but he objected to other chemical or artificial dyes. Cotton insisted on more colors. A compromise was reached wherein the only aniline dyes they would sell would be red, blue and black. Cotton succeeded in having a dye manufacturer, Wells & Richardson of Burlington, Vermont, put up dyes in small packages ready for their use. Later these became the famous Diamond Dyes, combining dye and mordant in one package which had only to be thrown into boiling water, envelope and all, and the wool boiled in the solution until the proper color was attained. There was no need to add vinegar or alum to set the color.

Cotton soon had a brilliant idea. Why not sell the blankets the Navajo wove for wearing for use as rugs? This was a stroke of genius; it revolutionized the trade and greatly increased the potential market for Navajo blankets. Traders, in their effort to keep weaving alive since it was important financially to the Navajo, suggested new patterns and forms that appealed to Anglo customers.

In June of 1885 Cotton bought Juan Lorenzo Hubbell’s half interest in the trading post at Ganado and all interest in wool owned by the partnership. He opened a business in Gallup, New Mexico, while continuing to work at Ganado. In 1896 he published an illustrated and descriptive catalogue of the Blanket and continued to expand his business.

By 1899 Hubbell was again the owner, and he built a trading empire which included 14 trading posts, wholesale warehousing, and freighting. His reputation gained him the title, “the greatest of all Indian traders.” He managed his vast holdings for over three decades, until his death in 1930.

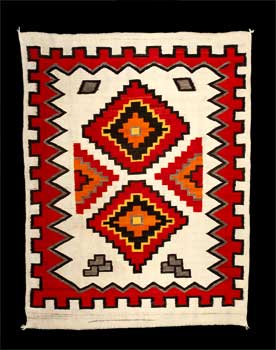

THE RUG: The famous Ganado “red” is perhaps the best known of all Navajo rugs, considered by most non-Indians what a Navajo rug should look like. Its creator, Juan Lorenzo Hubbell, specialized in a well-woven product that featured a brilliant red background surrounded by strong geometric crosses, diamonds, and stripes colored with yarns of gray, white, and black. Hubbell’s influence is still very much in evidence in the modern Ganado. The central motif is usually a bold diamond or cross, sometimes outlined in another color. Smaller forms occupy the remaining spaces. The rug can range from large, simple, bold designs to intricate, more sophisticated works. Some have contrasting borders along a pair of sides. The bright reds are still the dominant characteristic throughout the pattern, although recently the tones have taken on rich shades of burgundy. In some contemporary examples, various shades of gray are replacing the red backgrounds. Although bordered on the south by the vegetal-dye centers, the Ganado is a combination of the natural colors (grays and whites), the aniline dyes of black, and the characteristic red.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Pages 71, 72).

C.N. Cotton and His Navajo Blankets, by Lester L. Williams, M.D., 1989, Avanyu Publishing Inc., Albuquerque, NM (Pages 9, 23, 24, 33).

Source: Weaving of the Southwest, Marian Rodee, 1987, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, (Pages 98, 162).

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Location: 12 Miles south of Ganado, near the Defiance Plateau, Arizona.

THE RUG: An area identified with the Ganado, but sometimes subdivided into a separate regional style center is Klagetoh to the south. The familiar red, black, gray-white influence is evident. In contemporary weaves, the Klagetoh rug has not achieved the individualism to warrant regional recognition.

Klagetoh Trading Post has achieved some measure of publicity from retailers calling a certain type of Ganado, a ‘Klagetoh’. Some current arguments insist that the ‘Klagetoh’ is more sophisticated than the Ganado; that there is more design and complication in pattern; utilization of both vegetal and aniline dyes; elimination of the Classic crosses and diamonds; less red, more black, and so forth.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Pages 72, 73)

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Elevation: 5,364’

Location: Fifteen miles west of Teec Nos Pos lies the high, lonesome post of Red Mesa. (In Northeastern Arizona, near the Four Corners area)

Location: Fifteen miles west of Teec Nos Pos lies the high, lonesome post of Red Mesa. (In Northeastern Arizona, near the Four Corners area)

THE RUG: Here a small group of weavers are producing the Teec Nos Pos outline designs in traditional hand spun yarns of grays, white, black, maroons and dark red. Some writers have recognized the Red Mesa rug as a distinct regional style because of the local weavers’ dislike for bright colors. The design, however, despite the subdued tones, remains typical Teec Nos Pos.

Most typically, the Red Mesa weaving design consists of a line of chevrons running down the middle of the weaving surrounded by radiating serrated diamonds. The eyedazzler effect is created by laying a line of contrasting color against a lighter or darker color. The outlining of a figure in a drypainting with a line of contrasting color had ritual meaning. Likewise, weavers outlined a motif in one or even three or four colors popularly from 1880 to 1900 and still today in small numbers around the post of Red Mesa.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Page 44)

Source: Weaving of the Southwest, Marian Rodee, 1987, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, (Page 143)

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

“Circle of Cottonwoods”

Elevation: 5450’

Post Office Established: 1961

First Trading Post established in 1905

Location: West of Shiprock (Shiprock is located on the San Juan River in extreme northwestern New Mexico), gateway to the Four Corners region. (Arizona)

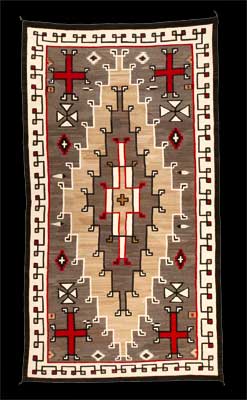

THE RUG: The dedicated weavers of Teec Nos Pos produce a tightly woven rug that has been described by many as the “least Navajo” of all the regional styles. The rug has a Persian flair, probably devised by an early trader who circulated examples of this style among the area craftswomen. Trader Noel took no credit for the design, and according to Maxwell, was convinced that Mrs. Wilson, a San Juan missionary, was responsible for influencing the weavers in this style.

THE RUG: The dedicated weavers of Teec Nos Pos produce a tightly woven rug that has been described by many as the “least Navajo” of all the regional styles. The rug has a Persian flair, probably devised by an early trader who circulated examples of this style among the area craftswomen. Trader Noel took no credit for the design, and according to Maxwell, was convinced that Mrs. Wilson, a San Juan missionary, was responsible for influencing the weavers in this style.

The Teec Nos Pos rug is very busy and intricate in design. Colors, often used in small amounts, are rather flamboyant. Bright greens, blue, orange, and reds are popular. Commercial yarns are more often used, with some utilization of aniline-dyed, handspun fibers. The typical Teec Nos Pos possesses a broad border that contains a design, usually a broad H, T, or L blocking. The rug primarily features a contrasting color outline of the main patterns which usually consist of zig-zag, serrated diamonds, triangles, and boxes. Because of its usually bright, multiple colors, the Teec Nos Pos is more difficult to blend into home decorating schemes. It is therefore more popular as a collector’s item.

Fifteen miles west of Teec Nos Pos lies the high, lonesome post of Red Mesa. Here a small group of weavers are producing the Teec Nos Pos outline designs in traditional hand spun yarns of grays, white, black, maroons and dark red. Some writers have recognized the Red Mesa rug as a distinct regional style because of the local weavers’ dislike for bright colors. The design, however, despite the subdued tones, remains typical Teec Nos Pos.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Pages 41, 42, 44)

Source: The Rugs of Teec Nos Pos: Jewels of the Navajo Loom by Ruth K. Belikove, Adobe Gallery, Albuquerque, NM

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Elevation: 5920’

Location: Situated on a treeless pediment separating the Chuska Mountains to the west from the Chaco wastelands, the site appears on 19th century maps as Crozier. (New Mexico). The name, Two Gray Hills, was probably derived from the Indian name, Bis dahlitso, which means, “upper yellow adobe.” Actually, there are several hills which backdrop the post and the color is tan, not gray.

Established: 1897

THE RUG: With the collapse of Moore’s rug dynasty at Crystal, (he left the trading post in 1911; however, a second mail order catalog was published at that time, and that business continued), some of his original designs filtered eastward through the snowy confines of Washington Pass to be nourished by the Two Gray Hills weavers. The area women eliminated Moore’s bright colors, especially the red, and began to produce a distinctive rug of their own. The Style was fully developed by the 1920’s and has remained little changed throughout the century. By 1925, the design elements borrowed from Moore had disappeared. Davies, now sole owner at Two Gray Hills, and Bloomfield (Toadlena), were responsible for this, as they spent many patient hours pointing out to their weavers the fine points of individual style and quality craftsmanship. What resulted from the efforts of these two dedicated traders was emergence of one of the finest textile styles to come – post-Revival loom, the Two Gray Hills Rug. Reportedly Bloomfield and Davies also showed their weavers potsherds from the general area as an inspiration for their rugs. These sherds would have been Anasazi black on white types as are found at Chaco Canyon. Especially noticeable in both rugs and pottery is a multiple-outlined Z shape.

THE RUG: With the collapse of Moore’s rug dynasty at Crystal, (he left the trading post in 1911; however, a second mail order catalog was published at that time, and that business continued), some of his original designs filtered eastward through the snowy confines of Washington Pass to be nourished by the Two Gray Hills weavers. The area women eliminated Moore’s bright colors, especially the red, and began to produce a distinctive rug of their own. The Style was fully developed by the 1920’s and has remained little changed throughout the century. By 1925, the design elements borrowed from Moore had disappeared. Davies, now sole owner at Two Gray Hills, and Bloomfield (Toadlena), were responsible for this, as they spent many patient hours pointing out to their weavers the fine points of individual style and quality craftsmanship. What resulted from the efforts of these two dedicated traders was emergence of one of the finest textile styles to come – post-Revival loom, the Two Gray Hills Rug. Reportedly Bloomfield and Davies also showed their weavers potsherds from the general area as an inspiration for their rugs. These sherds would have been Anasazi black on white types as are found at Chaco Canyon. Especially noticeable in both rugs and pottery is a multiple-outlined Z shape.

Novices to the field of Navajo weaving are often under the mistaken impression that the term “Two Gray Hills” refers to the color and pattern of the rugs bearing that name. In fact the “two gray hills” are actual landmarks near the trading post, but are not depicted in any of the rugs from this area.

The Two Gray Hills fabric is a bordered rug (usually in black), utilizing natural wool tones of blended white, brown, and black. With the exception of black, no commercial or vegetal dyes are used. The warm beige which is today associated with Two Gray Hills weaving was found all over the reservation in the period between 1920 and 1940. Both old and new rugs from Two Gray Hills are identifiable by certain characteristics, including a plain black outer border, multiple inner borders, a central medallion or double medallion with many hook motifs, and small filler elements (such as bars and dashes found in triangular elements).

Inch by inch and foot by foot, the Two Gray Hills rug is the finest textile to come out of Navajoland today (c. 1976). It is also the most expensive. One of the most attractive characteristics of the finer rugs is the light weight, accounted for by extremely careful carding and spinning, resulting in a high thread count in weaving. A weft count of 110 or more generally qualifies a rug as a tapestry. Some of the outstanding examples of Two Gray Hills rugs count in excess of 120 wefts to the inch.

A new style was developed in the 1970’s by Bruce Burnham of Burntwater, Arizona. Called “Burntwater” after his post, this style combines vegetal dyed wools of the revival style with the elaborate Two Gray Hills patterns. Soon, this style has taken over the former position of Two Gray Hills as the most expensive of all the Navajo weavings.

The evolution of the weaving style in the Two Gray Hills area has been the result of interaction among various groups – the trader with the customer, the trader with the weaver, and generations of weavers with one another. Older women pass on their traditions, younger women take the family traditions and add something of their own and slowly over the years this complex interaction produces visual changes.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Pages 58, 5

Source: Weaving of the Southwest, Marian Rodee, 1987, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, (Pages 99, 222, 225, 237)

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Elevation: 6000’

Location: In the juniper-forested hill country separating Chinle Valley from the Rio Puerco lies the trading center called Wide Ruins, named for the great Anasazi ruin, Kinteel, and situated on the grounds of Kinteel. (Arizona)

Established: In the early 1900s. In October of 1938, William and Sallie Lippincott purchased what was then called Kinteel Trading Post. The Lippincotts deserve the credit for improving and publicizing the rug industry in the southeast corner of the Reservation. Their vegetal dye experiments and encouragement of master weaving resulted in a superior textile in the years that followed. Sallie kept on hand a current plant recipe book which weavers could consult; Bill promoted a two-room addition to the schoolhouse so that weaving classes could be taught to the younger women - promising to buy their class projects; and jointly, they conceived the idea of holding craft festivals which they hosted in their home, complete with refreshments, home movies, gifts for the children, and awards for the best weaving and silversmithing.

Except for an absence during World War II when Bill served as a naval commander in San Diego, the popular Lippincotts traded at Wide Ruins until the fall of 1950, when they sold out to the Navajo Tribe. A few years later the Foutz family assumed ownership, and the post was operated by Phil Foutz under the banner of Progressive Mercantile.

THE RUG: The Wide Ruins district is the second all vegetal dye center on the Reservation; it is also one of the most recent in regional recognition, being developed by Sallie Lippincott in 1939-1940. The quality of the rug owes its origin to a desire of the Lippincotts to revitalize a poor rug market among the area weavers. At Sallie’s personal preference and insistence, the traders began their program by announcing that they would no longer buy a rug with a border. Undoubtedly influenced by McSparron and the Chinle success, they discouraged elaborate designs, and instead promoted simple horizontal stripes and bands constructed of total vegetal colors and handspun wool.

The Wide Ruins rugs that are produced today continue in fine workmanship; all handspun, beautifully dyed and woven. The natural colors of gray and white are used sparingly, but the blending of subtle shades of seemingly endless plant combinations, defies description. Soft pastels of exquisite pinks, yellow, beige, deep corals, rich grays, olive greens, multiple tones of tans and browns and hues of lilac all combine to make the Wide Ruins rug a popular choice.

To complement the colors, the Wide Ruins weaving design is Early Classic Period stripes and bands situated across a borderless product. Overall simplicity is intended, although ornamentation is quite complex. Finely constructed outlines, hatch work, “wavy lines” insertions, and beading techniques usually provide extraordinary embroidery arrangements. The panel designs are simplified forms of arrows, chevrons and squash blossoms. The attention to detail in the design approaches true artful expression.

As evidenced by their product, Wide Ruins weavers practice their craft with the utmost diligence, always striving for quality construction and continually searching for the yet undiscovered tinge that might lie in the dye-bath of a wild plum or juniper seed.

Source: Posts and Rugs, The Story of Navajo Rugs and Their Homes, by H. L. James, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Third Printing 1979; Copyright 1976 by Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. (Pages 78, 80, 81)

~~~~~Back to the Top~~~~~

Klagetoh Trading Post

Klagetoh Trading Post